Honourable editor of ‘Jurista Vārds’, Madam Gailīte, authors contributing to ‘Jurista Vārds’ and its readers, dear friends,

I

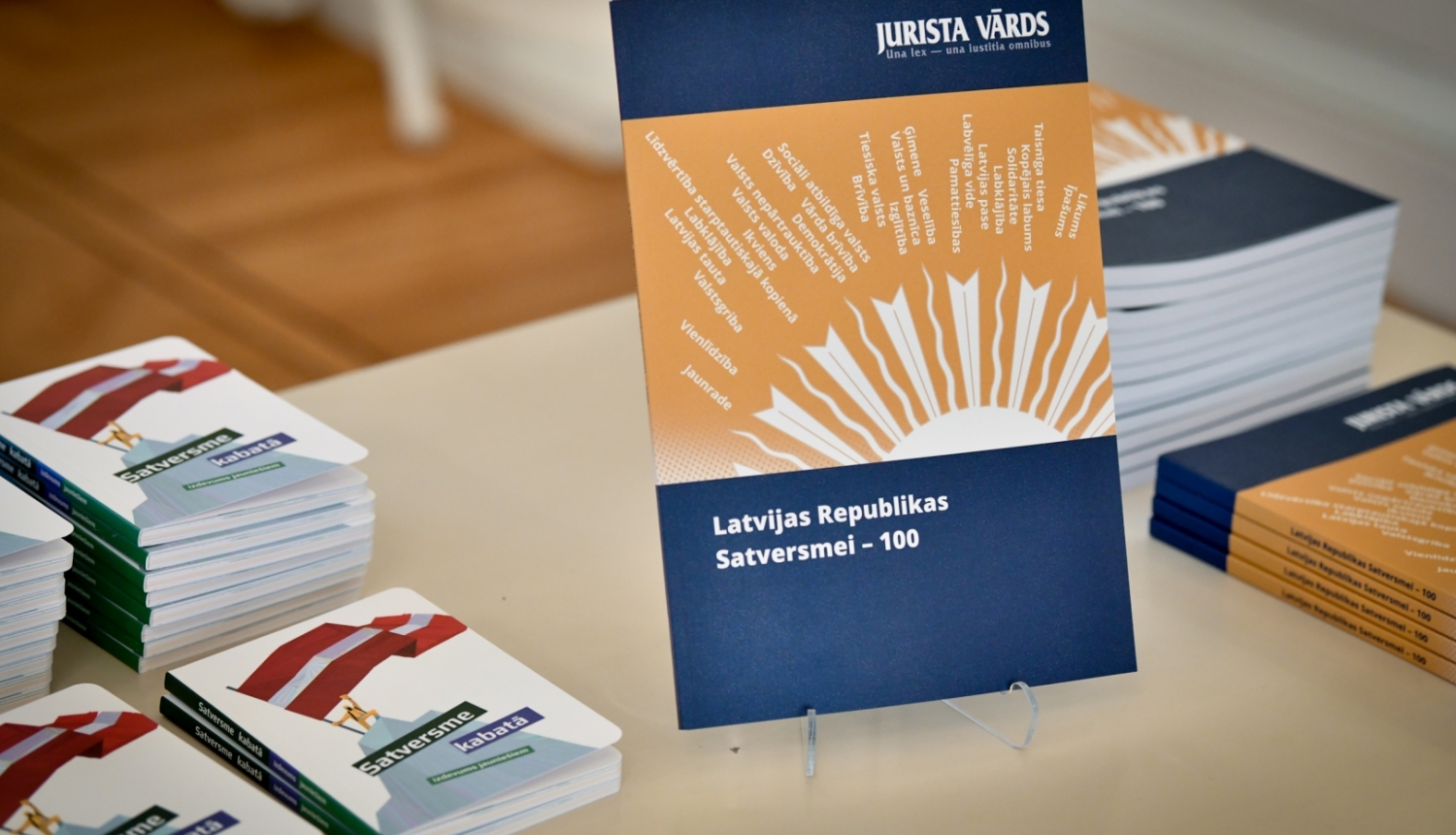

Let me open the discussion of authors published in the essay compendium created by ‘Jurista Vārds’ to mark the centenary of Satversme today by first thanking everyone who made this special publication possible – every member of ‘Jurista Vārds’ editorial team and especially contributing authors. I, as well, had the opportunity to contribute to this milestone project.

Film ‘Reading Satversme’ is another milestone initiative which gave people an opportunity to read one of the articles of our constitution. This film gives viewers a nice opportunity to appreciate the actual length and true meaning of Satversme. And, again, I have to thank the editorial team of ‘Jurista Vārds’ and Constitutional Court for collaborating on this exciting project.

100 years of Satversme had been this year’s focus of all legal professionals and many institutions, including Constitutional Court, Saeima, office of the President of Latvia and many others. This is the first celebration of our constitution of such magnitude. And rightly so – it is the fundamental legal document of Latvia and in many ways its history is far more interesting and unique than that of any other legal document. It is, for example, a document that remained legally valid throughout five decades of occupation of Latvia, forming the foundations of our state. Satversme was in an especially peculiar position between 1934 and 1940.

Although views differ, it is key to remember that Satversme is the very basis of our legal pyramid. Rights provided therein are interpreted by Constitutional Court, but other legal experts also work on their interpretations. Government bodies, of course, are also required to explain how laws work.

Professor Peter Häberle offers a theory on the community of interpreters of the meaning of Satversme. According to this theory, everyone who is active in particular field can add to a certain interpretation of Satversme. For instance, if I go to a kiosk and buy a newspaper, I become a part of interpretation, or manifestation, of constitutional provisions on buying products on free market – that is my right. Civil Law is also an example of system that needs constitution as the basis, and so on. As we celebrate the centenary of Satversme, we all join the community of constitutional interpreters of Satversme.

II

Satversme is very concise – an advantaged recognised by everyone. On the other hand, such concision allows for more interpretations, giving more power to Constitutional Court and others. The shorter the wording, the more room for manoeuvre the agent interpreting it will have. Parliament also has more flexibility in deciding which laws need to be adopted because they adhere to constitutional norms.

Powers of our Constitutional Court are much broader than those of similar institution in countries with very detailed constitutions. Let me mention two of them. One example is Greece, which has extremely nuanced constitution and whose Council of State therefore has extraordinarily little room for interpretation. Another example in comparative law is Portugal and its constitution. Also very detailed, unlike ours.

There are very few constitutions you could call ‘concise’. One is the Constitution of the United States of America adopted more than 200 years ago. Most constitutions of that era were similarly concise and Satversme followed the established trend.

III

But let me also mention another important constitutional concept that is more relevant than ever – self-defending or defensive democracy, which has also been described in Satversme. The world slipped into a kind of democratic euphoria after the global transformation in the 1990s. People thought that another period in human history has ended and the world will now be ruled by democracy. Because it is sensible and matches the human nature like no other system. Everyone expected democracy to lay foundations also in countries that were not democratic.

As we can see, people were wishful and this euphoria did not last long. In Europe, democracy is threatened by two kinds of dangers. Internal and external.

IV

We all know what external dangers are when we see an unprovoked attack of an authoritarian state on democratic Ukraine. Nobody believed this could ever happen. There have been several wars after the World War II, but none of them saw another country attacking a democracy, undermining its very existence as a state. Something we have not seen since the war ended. Apparently, it is still something we should expect in the 21st century. Our western allies were taken aback by what happened because no one except us here in the Baltics could have foreseen what would happen.

Now the world is confronted with this war. We are forced to defend our state and also our democratic political system that is being attacked from outside and from outside attempts to tear it down. This is the external dimension of self-defending democracy that requires enormous resources of all kinds from a state and its national defence framework.

Luckily, we belong to the most powerful defence alliance in the world, which unites 30 and soon 32 countries that are committed to making NATO’s norther flank even stronger. Collectively NATO is a lot stronger than the aggressor – Russia. It is up to our political will and determination to use this military, economic and political asset to stop Russia from attacking, and deterrence policy against Russia is one of the issues on the agenda of NATO.

V

And then there is also the internal security dimension, a dimension we usually refer to when talking about self-defending democracy.

Constitutional experts have been familiar with this concept for ages. What is more interesting is that this concept, which already existed in the European legal area, was reintroduced in part thanks to our efforts. One of Latvian residents had complained to European Court of Human Rights and lost the case because ECHR sided with Latvia and its position regarding the self-defending democracy. Thus, the internal dimension of self-defending democracy became a part of ECHR case-law and returned to European legal area.

This dimension is based on the principle that the freedoms offered by democracy cannot be used to abolish democracy.

I suppose constitutional experts, including Constitutional Court, should further develop this concept due to current geopolitical environment. This is how Latvia can help create a more robust European legal space. Some of our constitutional ideas are more sophisticated than in other European countries where such concepts (internal defence mechanisms of democracy) are less developed.

Let me also mention social rights, a section of subjective rights significantly broadened by the case-law of the Constitutional Court during the crisis. It is not common to stipulate such social rights in constitution in other countries of European legal area. This is another contribution of our constitutional system and Constitutional Court to more robust European legal area.

VI

Once again, thank you to all authors and everyone who helped make this idea possible. This publication, the compendium of essays, is a good way for the readers who are not experts in this field to better understand how Satversme applies to their daily life. It is a digest that enhances the understanding of constitutional principles and makes our legal system only stronger. Thank you all for that!